Chapter 4

Mexicano Stories and Rural White Narratives: Creating Pro-Immigrant Conservatism in Rural Georgia, 1965-2004

The Oxford English Dictionary defines “archive” as “a place in which public records or other important historic documents are kept.” While historians have typically worked in the official archives of governments, universities, and other institutions, living individuals can also be sources of archival material drawn from their own or their forebears’ experiences. Chapter Four of Corazón de Dixie delves into the relationship between white Christian volunteers and Mexicano migrants in the 1980s-2000s. Two such volunteers, Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman, saved their own archive of documents from their work with Mexicano migrants, including several letters that migrants sent them after leaving Georgia.

Pages 166-7 of Corazón de Dixie examine these letters to interpret their writers’ feelings about the Thurmans and their outreach work. But what else can you learn about the values, perspectives, and lives of each of the three letter writers based not only on their content, but also their physical form and style of language?

Primary Sources

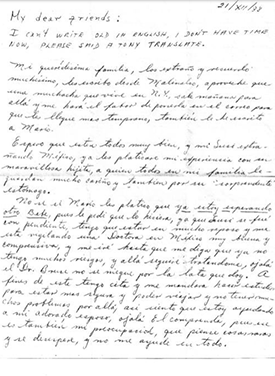

Letter from Margarita to Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman, Personal papers of Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman.

This letter from a woman named Margarita to Howdy and Mary Ann reveals insights about the experiences of women migrants in the late 1980s – exactly the period when female migration from Mexico began to increase.

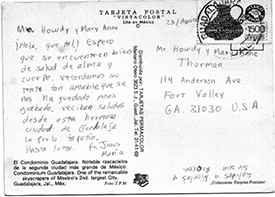

Postcard from Jesus María to Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman, c. 1990, Personal papers of Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman.

Now living in Guadalajara, Jesús María represented the increasing numbers of Mexicans, an of Mexican migrants, who lived in cities in the late twentieth century (see pages 189-90 of Corazón de Dixie). Consider the image or message he may have been sending to Howdy and Mary Ann when he selected this postcard to send them.

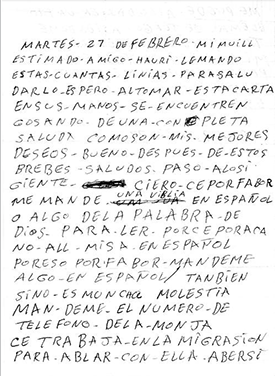

Letter from Eujenio Moreno to Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman, 1990, Personal papers of Howdy and Mary Ann Thurman.

At first glance, even Spanish speakers may find Moreno’s letter difficult to read. It does not use standard spellings of words, nor standard punctuation – probably reflecting Moreno’s limited formal education. Yet, this is precisely what makes the letter so valuable. Moreno’s letter offers the firsthand perspective of a marginally literate migrant – exactly the kind of person whose perspective historians often struggle to reconstruct. Try reading the letter aloud and you will find that his message makes sense when absorbed aurally. As with all documents in a language you don’t understand perfectly, don’t become frustrated if every point isn’t immediately clear. Instead, keep going to see what you can learn about Moreno, his priorities in his new location of McAlpin, Florida, and his world view.

For further help reading this letter in Spanish, see Tips on comprehension