Chapter 1

Mexicans as Europeans: Mexican Nationalism and Assimilation in New Orleans, 1910-1939

Chapter One of Corazón de Dixie discusses the assimilation of Mexican immigrants into the white side of the New Orleans color line between 1918 and 1939. To do this, it relies in large part on manuscript census pages. Americans today are accustomed to filling out their own census forms. But prior to 1960, Census bureau employees, known as enumerators, went door to door filling them out (and thus, bringing their own assumptions to the table). These manuscript census pages, available in microfilm at public libraries or else via websites like Ancestry.com (which is often free to use from a public or university library), are a great resource for historians who wish to understand the social and economic details of people’s lives in the past.

Look through the manuscript census pages here and consider them in the context of your knowledge about this particular time and place. What new stories can you tell about the lives of Mexicans and Mexican Americans in New Orleans around 1930, beyond those already offered in the book? Can these individual stories help you to draw any larger conclusions about New Orleans’ Mexicanos as a whole?

Be sure to read through the guide to the 1930 Census and look at the blank form first, to help you understand the actual primary documents.

Primary Sources

Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930 “Understanding the 1930 U.S. Census”

This guide prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau will help you interpret manuscript census pages.

Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930“1930 Census Form”

It can often be difficult to read scans of census forms from Ancestry.com. Keeping this blank form handy will help you know which column you’re looking at.

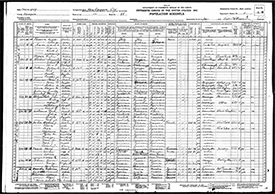

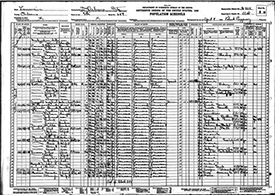

Sinforina Anarda household, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, New Orleans, La., Enumeration District 36-200, Sheet 2B, accessed via Ancestry.com

Anarda’s household is listed at the very bottom of the page; as you can see, she and her lodger Samuel Andrete were “Hot Tamale” salespeople. While it’s still unclear exactly how tamales found their way to the U.S. South, the Southern Foodways Alliance provides useful speculation. Notice how you can learn about Anarda’s migrations by looking at the birthplaces of her sons and their father.

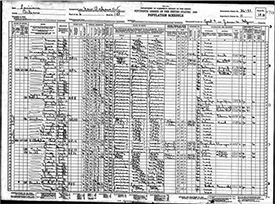

Raymond and Marianna Borga household, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, New Orleans, La., Enumeration District 36-99 Sheet 10A, accessed via Ancestry.com

The Borga household is listed at the very bottom of the page. Note the Census enumerator’s evident confusion over the racial classification of the Borga family as well as the Italian family of “Papa Sam” down the block. Also consider the make-up of their neighborhood, immigration year, and Raymond’s profession in the context of interwar New Orleans and Mexican migration as described in Corazón de Dixie.

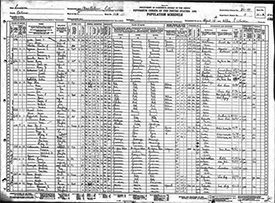

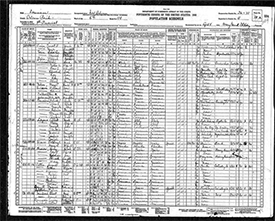

Manuel Derminy household, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, New Orleans, La., Enumeration District 36-212 Sheet 8B, accessed via Ancestry.com

The two Mexicanas on this page are in the household of Manuel Derminy, an African American: his wife María and his mother-in-law (María’s mother) Francisca Abelarda. As you can see, the entire family including María was racially classified as Negro, with the exception of Francisca, who was classified as Mexican. Table 4 (page 32) in Corazón de Dixie shows that it was very unusual for Mexicanas in New Orleans to marry black men; nonetheless, this page from manuscript census allows historians to learn more about lives of these mixed families.

Christ Villalabos household, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, New Orleans, La., Enumeration District 36-97, Sheet 10B, accessed via Ancestry.com

The household of Christ Villalobos, his wife (whose name is difficult to make out in the enumerator’s handwriting) and their son Elías somehow confused the enumerator (note the question marks around their birthplaces). Furthermore, though they’d apparently crossed the border just five years beforehand, all three are listed as speaking English and Christ was the proprietor of his own shoe repair store. One possible role of the historian is to use knowledge of the time and context to create a narrative from such bits of inconclusive information.

Anthony Blasco household & Samuel Pattin household, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, New Orleans, La., Enumeration District 36-71, Sheet 10A, accessed via Ancestry.com

Mexicanos appear in two households on this census page. There was musician Anthony Blasco, married to a Florida-born white woman. Farther down the page in the household of Samuel Pattin lived his wife, Louisiana-born Mexicana Bertha Pattin, and her brother, Mexican-born Miguel Laquett. Once again, the messy notations of the enumerator suggest confusion about the racial classifications of all four. The neighborhood as a whole seems to be largely working-class, as evidenced by the professions of its inhabitants. Both entries can provide insight into the lives of families that included both white and Mexicano members.