Chapter 3

Citizens of Somewhere: Tejanos, Braceros, Dixiecrats, and Mexican Bureaucrats in the Arkansas Delta, 1939-64

Chapter Three of Corazón de Dixie discusses Mexican workers’ struggles for rights in the Arkansas Delta. These workers drew two federal governments into their struggles to receive the wages, housing conditions, and medical attention that their bracero contracts had promised them. They also insisted on admission to white public spaces in the era of Jim Crow. Fortunately, federal government records from decades past are typically among the most readily accessible to historians. After examining these documents from Mexico’s Secretariat of Foreign Relations archive, officially known as the Archivo Histórico Genaro Estrada de la Dirección General del Acervo Histórico Diplomático de la Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (AHSRE), consider the following question:

What were Mexican government officials’ expressed motivations for stopping anti-Mexican discrimination in Arkansas, and how did they differ from the motivations of U.S. employers and government officials?

For help reading untranslated letters in Spanish, see this Guide to interpreting Mexican government letters and these tips on comprehension.

Primary Sources

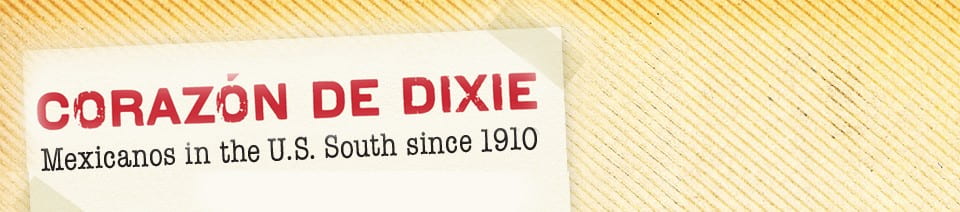

Rubén Gaxiola to SRE, November 19, 1949, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

In this letter, the head of Mexico’s consulate in Memphis, Rubén Gaxiola, writes to his superiors in Mexico City to confirm a telegram he’d sent a week beforehand, in which he’d alerted them to the discrimination Mexicans faced in Marked Tree, Arkansas. He attaches 11 photos of anti-Mexican signs he found there. You can read a translation here; pay attention to Gaxiola’s tone, reasoning, and the evidence he presents.

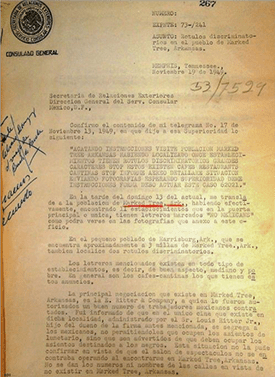

Director General Manuel Aguilar to Consul of Mexico in Memphis, November 17, 1949, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE

In this letter, a Mexico City bureaucrat, Manuel Aguilar, reports that he received the Memphis Consul Rubén Gaxiola’s telegram of November 13, 1949, regarding anti-Mexican discrimination in Marked Tree, Arkansas. Aguilar instructs Gaxiola to alert U.S. authorities so that the situation can be corrected or, failing that, braceros removed from the area. Give some thought to what this response reveals about the Mexican government’s involvement in the bracero program at that particular time and place.

For help reading this letter in Spanish, see the Guide to interpreting Mexican government letters.

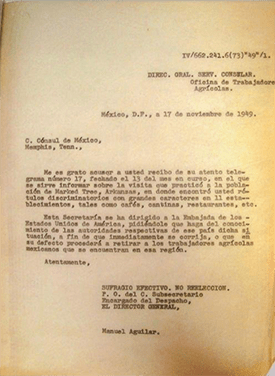

J.G. Waskom, Mayor of Marked Tree, to D.O. Rushing, Employment Service, Little Rock, November 21, 1949; folder TM-26-32 AHSRE

In this letter, the mayor of Marked Tree tries to convince the U.S. Employment Service’s local representative that anti-Mexican discrimination can be swiftly ended in Marked Tree. Note the arguments that he apparently used to convince businesses to remove their “No Mexicans” signs.

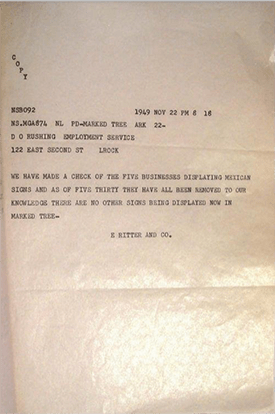

Telegram from E. Ritter and Co. to D.O. Rushing, Employment Service, Little Rock, November 22, 1949, folder TM-26-32 AHSRE

The brevity and style of this message from E. Ritter, Marked Tree’s largest employer of Mexican braceros, suggests that it was probably a copy of a telegram. He sent it to the local branch of the federal U.S. Employment Service, which oversaw bracero contracts from the U.S. side.

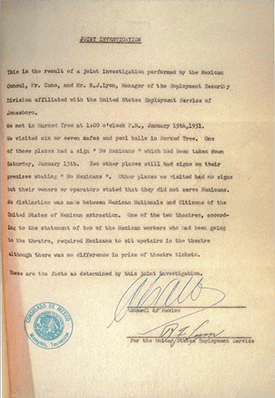

Joint Investigation of Consul Cano and United States Employment Service, January 15, 1951, folder TM-26-2, AHSRE

Joint Investigations like this one were common responses to allegations of bracero contract violations in the early 1950s. Representatives from the U.S. and Mexican governments would meet up at the bracero work location and produce a joint report of what they found there. By the late 1950s, such cooperative documents were less common. The Mexican government had largely lost control over the program, for reasons explained in Chapter 3 and the other scholarship it cites.

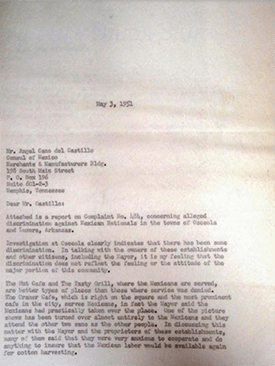

D.O. Rushing, Agricultural Employment Specialist, to Angel Cano, May 3, 1951, folder TM-26-2, AHSRE.

In this letter, the U.S. government’s representative confirms to the Mexican consul in Memphis, Angel Cano, that new complaints against discrimination in Osceola, Arkansas are in fact well-founded. He reports on local officials’ eagerness, however, to correct the problem; pay attention to the reasons they give for their willingness to cooperate.

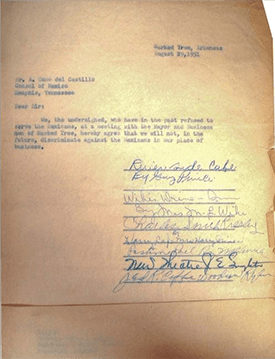

Declaration to A. Cano de Castillo, August 29, 1951, folder TM-26-2, AHSRE.

The declaration is signed by local business owners who pledge to stop discriminating against Mexican immigrants. Note the reasons they cite for doing so.

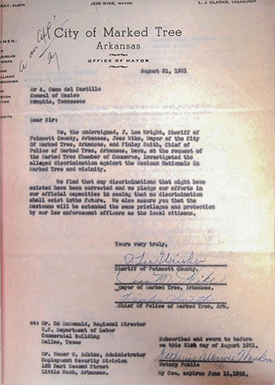

Sherriff of Poinsett County, Mayor of Marked Tree, and Chief of Police, Marked Tree, to Cano de Castillo, August 31, 1951, folder TM-26-2. AHSRE

In this letter, Marked Tree’s local officials claim that anti-Mexican discrimination has ended, and they pledge to ensure it will not return in the future. Note their use of the word “citizens”—what is it code for?

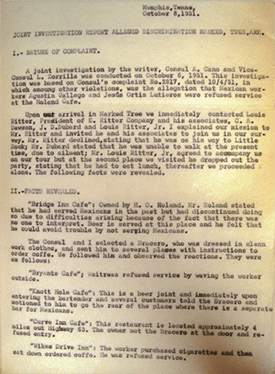

Joint Investigation Report Alleged Discrimination in Marked Tree, Arkansas, October 8, 1951, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

This joint investigation report is longer and more detailed than Document 3.5. It includes a “secret shopper experiment” in which U.S. and Mexican government officials watched how a particular bracero was treated in different establishments. Notice the reasons the business owners gave for discriminating against Mexicans.

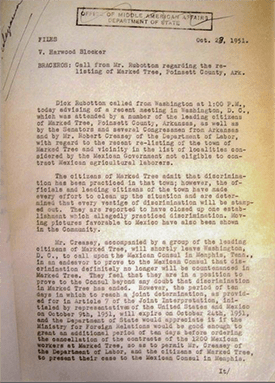

Consular report from V. Harwood Blocker, October 28, 1951, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

This document shows the international scope of the Marked Tree dispute: Arkansas planters have gone to Washington, D.C. to plead for help convincing the Mexican government to help them contract braceros again and Blocker, an official at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, has gotten involved.

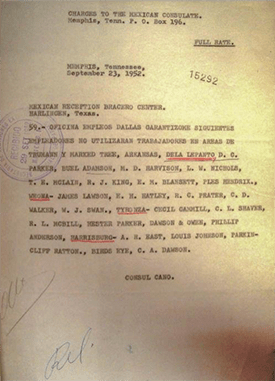

Consul Cano, Memphis, to Mexican Bracero Reception Center, Harlingen, Texas, September 23, 1952, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

This is a copy of a telegram Consul Cano sent to the bracero reception and contracting center on the Mexico-U.S. border. In it, he tells his colleagues not to contract braceros to Arkansas towns and employers that have broken the bracero contracts, likely due to discrimination and/or poor labor practices. Telegrams like these were the mechanism through which the Mexican government could enforce its threat of blacklisting agricultural areas and employers from the bracero program.

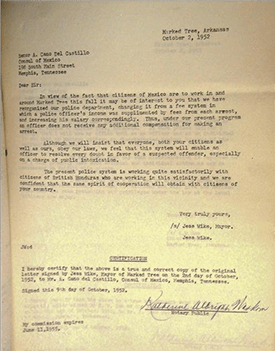

Jess Wike, Mayor of Marked Tree, to Cónsul A. Cano de Castillo, October 2, 1952, folder TM-26-2, AHSRE.

In this letter, the mayor of Marked Tree explains to Consul Cano how a new police compensation system should discourage arrests of braceros.

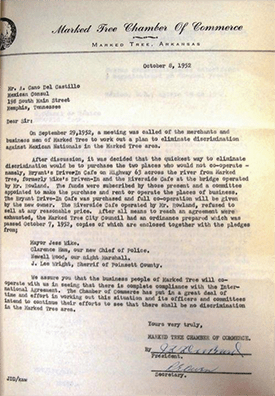

Marked Tree Chamber of Commerce to A. Cano de Castillo, October 8, 1952, folder TM-26-2, AHSRE.

In this letter, the Marked Tree Chamber of Commerce details its extensive efforts to combat anti-Mexican discrimination in their town. How can the description of these efforts help us understand the nature of anti-Mexican sentiment in Mark Tree?

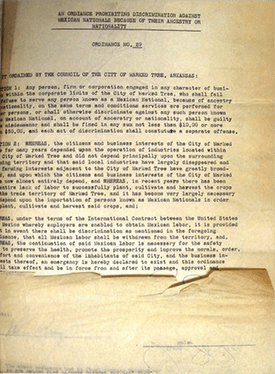

Ordinance #29 – An Ordinance Prohibiting Discrimination against Mexican Nationals Because of their Ancestry or Nationality, October 9, 1952, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

As is often the case with archival documents, it was not possible to read every word of this one without damaging the document itself. Nonetheless, do your best to understand the content and expressed motivations behind this local ordinance.

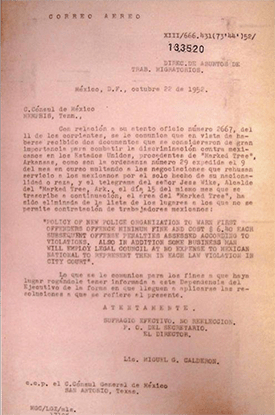

Miguel Calderón, Director of Office of Migratory Workers, to Consul of Mexico, Memphis, October 22, 1952, folder TM-26-32, AHSRE.

Miguel Calderón, a Mexico City-based official in the Secretariat of Foreign Relations, is finally convinced that discrimination in Marked Tree has stopped, and is willing to restart bracero contracting to the area. Speculate as to possible reasons why he might have made this decision.

For help reading this letter in Spanish, see the Guide to interpreting Mexican government letters.